A look at the historical drivers of battery profitability

We often hear people talk about volatility in the NEM: ‘the market has been volatile lately’, ‘we’re expecting some volatility this afternoon’, and so on. Moreover, there is a direct connection that is often drawn between volatility and the business case for batteries. But there is no unified view as to what we mean by volatility, and how we can measure it.

In this article, we examine the historical outcomes for three different definitions and attendant measures of volatility. We then seek to answer the question: is the NEM becoming more volatile, and what does this mean for batteries?

Volatility measure 1: High prices

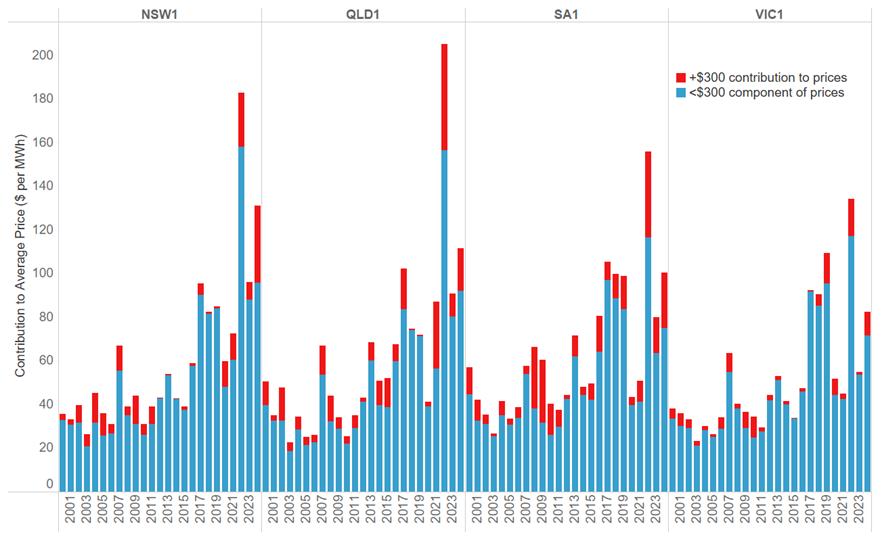

Our first measure is an old favourite – the contribution of prices above $300 per MWh to average prices. Chart 1 shows this analysis for all mainland regions of the NEM on a calendar year basis for 2000 to 2024. We note the following:

- NSW and Queensland have just seen their highest prices in history save for the 2022 Energy Crisis. Outcomes in South Australia are also near record highs, and Victorian prices are at their highest level since the period following the closure of Hazelwood.

- The 2024 +$300 per MWh component of prices is at record levels in NSW, and has been at its highest level in around 15 years (save for 2022 Energy Crisis) in South Australia, moderate in Queensland, and a little above average in Victoria.

Chart 1 – Scarcity prices have been rising in importance over the last 5 years

Average prices in bands by region on a calendar year basis, 2010 to 2024

In general, the last 5 years has seen far more value in scarcity pricing across the NEM than at virtually any other period in its history, with the possible exception of 2008 and 2009 in South Australia.

Volatility measure 2: Opportunity for energy arbitrage

But high prices alone are not the only measure of volatility. People often refer to variability in prices as being a measure of volatility. For example, frequent periods of low prices followed by high prices are often perceived as being volatile periods, particularly because they give rise to the opportunity for energy arbitrage.

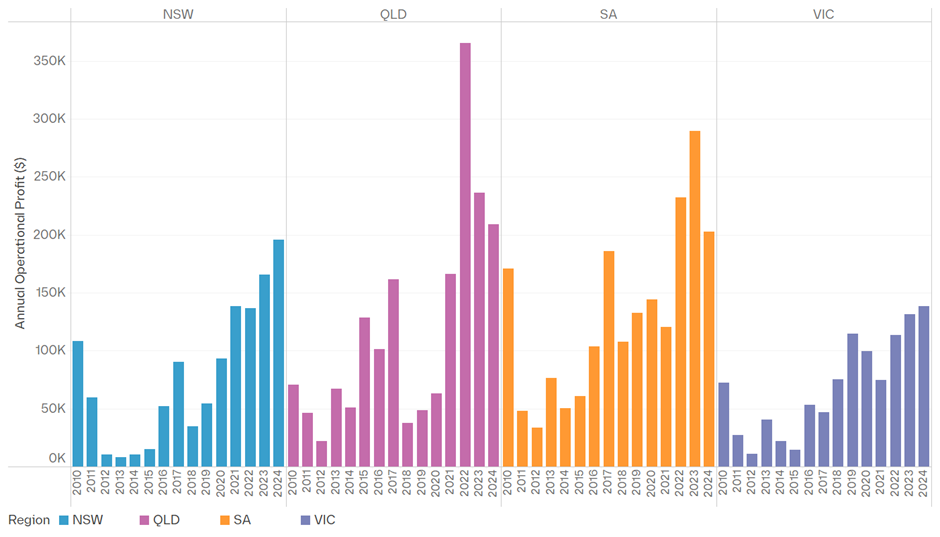

How do we measure this type of volatility and how it is changing over time? One way is to examine how a hypothetical price-taking battery would have performed over a given period. Chart 2 shows the calculated trading profit for a 1 MW, 2-hour battery operating with perfect foresight over the period from 2010 to 2024. The height of the bar shows how much a battery could have earned in revenue less the cost of charging.

Maximum energy arbitrage profit available for batteries has been rising steadily, and has seen record levels in NSW and Victoria in 2024. Similarly, the levels seen in Queensland and South Australia have been relatively high.

Chart 2 – Annual operational profit has been rising over the last 10 years

Annual operational profit for 1MW, 2-hour battery, 2010 to 2024

Type 3 Volatility: Interval-to-interval variation

We have described two concepts of volatility, both of which are inherently linked to the concept of battery profit. But there is another more mathematical view of volatility – the concept of variation. Variation is defined as the cumulative interval-to-interval change in a time series. So if we consider the series (10, 20, 5, 40), the cumulative variation is given by:

abs(20-10) + abs(5-20) + abs(40-5) = 10 + 15 + 35 = 60.

We can then take an average of this, which yields 20 per step (ie, 60/3 steps). In the case of the NEM, we can look at the average variation in spot prices for a region, to get an indication of how much prices are rising and falling from one 5-minute interval to the next.

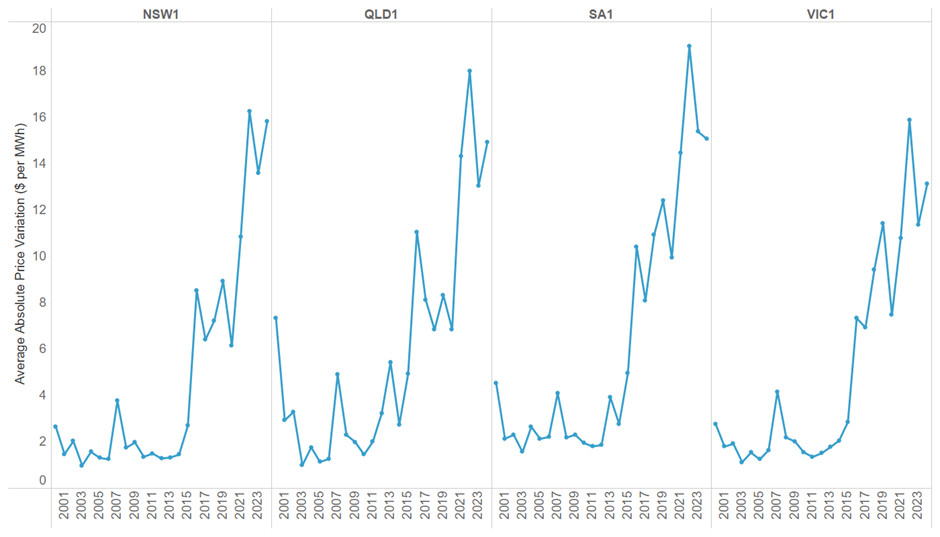

Chart 3 shows the average variation for each mainland region and for each calendar year from 2000 to 2024. To filter out the effect of scarcity pricing, we have capped prices at $500 per MWh, though we note that this does not affect the trend in the results.

Average variation has increased markedly over the last decade. Where previously prices were very stable, there are now regular rises and falls over the course of the day. On average, prices are changing by $15 per MWh every 5-minutes across all regions. Put simply, there is more noise in prices than ever before.

Chart 3 – Variation has been rising steadily over the last 10 years

Average absolute price variation by region on a calendar year basis, 2000 to 2024

This an astonishing result, which confirms what many NEM-watchers, who live and breathe the market have noticed for the last few years, ie, that prices are ‘going up and down’ more and more.

What are the consequences of this rise in variation of prices for batteries? All else being equal, adding noise to a price series increases the opportunity for arbitrage. That said, capturing the low and high points of a noisy price series is harder than capturing the low and high points of a more predictable price series. It follows that:

- The rise in variation has increased the potential profitability of batteries that operate on an energy arbitrage basis.

- A part of the profitability of batteries shown in Chart 2 can be attributed to the rise in variation.

- A question therefore remains as to how much of this interval-to-interval volatility can be captured by a battery.

The third point is particularly relevant, as it speaks to how much of the profitability that we see through backwards looking analysis could have reasonably been captured. Nevertheless, all else being equal, more interval-to-interval volatility is going to improve the business case for batteries, even if they cannot capture the entirety of the available arbitrage revenue.

Conclusion

We have looked at three measures of volatility, and each of them tells a different story about the outlook for batteries. But, regardless of how we define it, there has indeed been an increase in volatility in the market, as demonstrated by the following:

- An increased contribution of scarcity pricing over the last 5 years.

- A steady climb in the money on the table for 2-hour batteries from energy arbitrage.

- Record levels of interval-to-interval variation in prices.

Put simply, the odds have been shifting in favour of battery profitability. However, the immediate question is whether these trends will persist, reverse, or stabilise as the energy transition continues. We will consider this question in a subsequent article.